1637

End of the Pequot War

The Pequot War was New England’s first major conflict, involving thousands of combatants in dozens of battles in Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut. The final battle of the war, however, was fought in a swamp in what is now Southport. In late June 1637, the English organized a final campaign against the large groups of Pequot moving west towards the Hudson River under the leadership of their grand sachem Sassacus. The English-allied force consisted of 120 soldiers from Massachusetts Bay and 40 from Connecticut along with an unknown number of Native (Narragansett/Mohegan/”River Indians”) warriors. They embarked from Saybrook Fort, and first set sail for Long Island in pursuit of Sassacus. The attack force made landfall at Quinnipiac (present-day New Haven) and marched west along the shoreline in pursuit of groups of Pequot. The English eventually caught up with Sassacus’ group at Poquonnock (present-day Bridgeport) and tracked them to Sasquanikut, where the last major battle of the Pequot War took place. On July 13, 1637, the Great Swamp Fight was fought for 24 hours at Munnacommuck Swamp, known today as the Pequot Swamp. This battle put an end to the Pequot War. A memorial now sits on a small triangle of land between Post Road and Old Post Road in Southport.

The Pequot War was New England’s first major conflict, involving thousands of combatants in dozens of battles in Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut. The final battle of the war, however, was fought in a swamp in what is now Southport. In late June 1637, the English organized a final campaign against the large groups of Pequot moving west towards the Hudson River under the leadership of their grand sachem Sassacus. The English-allied force consisted of 120 soldiers from Massachusetts Bay and 40 from Connecticut along with an unknown number of Native (Narragansett/Mohegan/”River Indians”) warriors. They embarked from Saybrook Fort, and first set sail for Long Island in pursuit of Sassacus. The attack force made landfall at Quinnipiac (present-day New Haven) and marched west along the shoreline in pursuit of groups of Pequot. The English eventually caught up with Sassacus’ group at Poquonnock (present-day Bridgeport) and tracked them to Sasquanikut, where the last major battle of the Pequot War took place. On July 13, 1637, the Great Swamp Fight was fought for 24 hours at Munnacommuck Swamp, known today as the Pequot Swamp. This battle put an end to the Pequot War. A memorial now sits on a small triangle of land between Post Road and Old Post Road in Southport.

To find out more about the archaeology project on the Battlefields of the Pequot War, click here.

1639

Fairfield's Four Squares

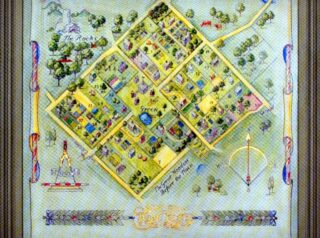

Fairfield was known until 1650 by its Native American name, Uncoway (the “place beyond”). It owes its existence as a European settlement to Roger Ludlow, an English Puritan who was a leader in the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut colonies. After the Pequot War of 1637 reduced Native American power in Connecticut, Ludlow purchased a large tract of land from the local Paugussett tribe in 1639 and encouraged a few English families to settle around what eventually became the center of colonial Fairfield. Laying out a set of perpendicular roads, Ludlow created four squares of about 30 acres each, comprising house lots. A town green stood in the center. Newton Square contained the parsonage land for the use of the minister. Frost Square was for the Meeting House, the Court House, and the School House. A third square, Burr Square, was for a military or public park with a place for a burying ground. The fourth square contained land for Ludlow. Although Ludlow left Fairfield in 1654 for Ireland, the physical imprint of his town plan was indelibly fixed upon the local landscape.

Fairfield was known until 1650 by its Native American name, Uncoway (the “place beyond”). It owes its existence as a European settlement to Roger Ludlow, an English Puritan who was a leader in the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut colonies. After the Pequot War of 1637 reduced Native American power in Connecticut, Ludlow purchased a large tract of land from the local Paugussett tribe in 1639 and encouraged a few English families to settle around what eventually became the center of colonial Fairfield. Laying out a set of perpendicular roads, Ludlow created four squares of about 30 acres each, comprising house lots. A town green stood in the center. Newton Square contained the parsonage land for the use of the minister. Frost Square was for the Meeting House, the Court House, and the School House. A third square, Burr Square, was for a military or public park with a place for a burying ground. The fourth square contained land for Ludlow. Although Ludlow left Fairfield in 1654 for Ireland, the physical imprint of his town plan was indelibly fixed upon the local landscape.

1684

Old Burying Ground

When the town of Fairfield was first designed in 1639, the land just south of the Fairfield Museum on Beach Road was set aside as a burying ground. The Old Burying Ground, as it is now known, seems to have been laid out in 1685. Many of its earliest graves are no longer marked, and the oldest surviving markers are simple undecorated stones with very little information. The oldest marked gravestone in the Old Burying Ground is inscribed “1687 S.M.” and is believed to mark the grave of Samuel Morehouse, who served as county marshal and lieutenant from 1675 to 1687. (We do not know for certain where Fairfielders were buried between 1639 and 1685, but it is likely that they were buried on their own land.) During the late 1700s and throughout the 1800s, gravestones became more sculptural and biographical. Designs reflected thoughts about death and the value placed on an individual’s life. The Old Burying Ground is the final resting place for many people prominent in Fairfield’s early history, including Andrew Ward, Samuel Penfield, Caleb Brewster, Thaddeus and Eunice Burr, Andrew and Hannah Wakeman, and Jonathan Sturges.

When the town of Fairfield was first designed in 1639, the land just south of the Fairfield Museum on Beach Road was set aside as a burying ground. The Old Burying Ground, as it is now known, seems to have been laid out in 1685. Many of its earliest graves are no longer marked, and the oldest surviving markers are simple undecorated stones with very little information. The oldest marked gravestone in the Old Burying Ground is inscribed “1687 S.M.” and is believed to mark the grave of Samuel Morehouse, who served as county marshal and lieutenant from 1675 to 1687. (We do not know for certain where Fairfielders were buried between 1639 and 1685, but it is likely that they were buried on their own land.) During the late 1700s and throughout the 1800s, gravestones became more sculptural and biographical. Designs reflected thoughts about death and the value placed on an individual’s life. The Old Burying Ground is the final resting place for many people prominent in Fairfield’s early history, including Andrew Ward, Samuel Penfield, Caleb Brewster, Thaddeus and Eunice Burr, Andrew and Hannah Wakeman, and Jonathan Sturges.

1692

Women Accused of Witchcraft

In 1692, while the Salem witch trials took place in Massachusetts, Fairfield had its own witch trial. On October 28, 1692 the trial of Goody Clawson and Goody Disborough was held in the county courthouse on the Fairfield Town Green. Katherine Branch, a servant living with Daniel and Abigail Wescott in Stamford, had become “possessed” and the cause was suspected to be witchcraft. She accused six women in total and two went to trial: Elizabeth Clawson of Stamford and Mercy Disborough of Compo (now Westport). Hoping to prove her innocence, Mercy asked: “to be tried by being cast into ye water.” Both women were taken to Edwards pond, bound hand to foot, and pushed into the water. At that time it was believed that a witch would float. Witnesses testified that both women “put into the water swam like a cork.” Despite this outcome, neither woman was executed. After many deliberations between the jurors, magistrates, ministers, and the colonial government in Hartford, the jury acquitted Goody Clawson but found Goody Disborough guilty. Fearing more hysteria, three magistrates granted Disborough a reprieve based on a technicality. Recent events in Salem, they wrote, “should be warning enough.” The Town filled in Edwards Pond in 1869, but you can still see a depression in the Green where it once stood, along with an interpretive marker.

In 1692, while the Salem witch trials took place in Massachusetts, Fairfield had its own witch trial. On October 28, 1692 the trial of Goody Clawson and Goody Disborough was held in the county courthouse on the Fairfield Town Green. Katherine Branch, a servant living with Daniel and Abigail Wescott in Stamford, had become “possessed” and the cause was suspected to be witchcraft. She accused six women in total and two went to trial: Elizabeth Clawson of Stamford and Mercy Disborough of Compo (now Westport). Hoping to prove her innocence, Mercy asked: “to be tried by being cast into ye water.” Both women were taken to Edwards pond, bound hand to foot, and pushed into the water. At that time it was believed that a witch would float. Witnesses testified that both women “put into the water swam like a cork.” Despite this outcome, neither woman was executed. After many deliberations between the jurors, magistrates, ministers, and the colonial government in Hartford, the jury acquitted Goody Clawson but found Goody Disborough guilty. Fearing more hysteria, three magistrates granted Disborough a reprieve based on a technicality. Recent events in Salem, they wrote, “should be warning enough.” The Town filled in Edwards Pond in 1869, but you can still see a depression in the Green where it once stood, along with an interpretive marker.

1750

Building the Ogden House

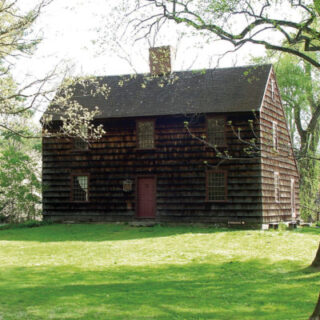

If you live in New England, chances are you’ve heard of a “saltbox” house. The saltbox-style home originated here in the 1600s and was given that name because the shape of the roofline of these houses resembled the wooden boxes in which colonists kept salt. The earliest Saltbox homes were created by simply adding a lean-to addition to the rear of an original 2-story house, but by the early 1700s, the design was seen as so successful, and so fitting the needs of the settlers in the Northeast, that builders began to build saltbox houses with the addition built right into the original design. Most saltbox homes have two stories in the front and one in the back, a sloping gable roof with unequal sides (sometimes with the back roof reaching as low as six feet) and a central chimney. The long, low pitch of the back of the roof was, where possible, planned to face North, to partially deflect the blowing snow and rain that frequently came along with the North wind. The Odgen House at 1520 Bronson Road in Fairfield, is an exceptional example of a mid-1700s saltbox home. During the spring of 1750, newlyweds David and Jane Sturges Ogden moved into their new home on the road to Greenfield. They had reason to look forward to their future. Both came from established families who could afford to start them out well in life. Jane brought a reasonable dowry and David’s family provided the house and land. For the next 125 years it was home for the Ogden family in the farming and coastal shipping town of Fairfield. Today, the Ogden House retains its beautiful situation overlooking Brown’s Brook in the fertile Mill River Valley. It contains fine furniture, spinning wheels, tableware, iron pieces, textiles, and other objects from the Fairfield Museum collections. An eighteenth-century style kitchen garden behind the house is laid out symmetrically with raised beds. The garden features herbs typical of those used at the time, and is generously maintained by the Fairfield Garden Club. A bridge across the brook leads to a trail planted with native Connecticut wild flowers and shrubs. In 2013 an apiary was established to respond to the Honey Bee Colony Collapse Disorder and to signify the importance of beekeeping in colonial times. Bee pollination insured the garden’s productivity — the key to surviving in colonial New England.

If you live in New England, chances are you’ve heard of a “saltbox” house. The saltbox-style home originated here in the 1600s and was given that name because the shape of the roofline of these houses resembled the wooden boxes in which colonists kept salt. The earliest Saltbox homes were created by simply adding a lean-to addition to the rear of an original 2-story house, but by the early 1700s, the design was seen as so successful, and so fitting the needs of the settlers in the Northeast, that builders began to build saltbox houses with the addition built right into the original design. Most saltbox homes have two stories in the front and one in the back, a sloping gable roof with unequal sides (sometimes with the back roof reaching as low as six feet) and a central chimney. The long, low pitch of the back of the roof was, where possible, planned to face North, to partially deflect the blowing snow and rain that frequently came along with the North wind. The Odgen House at 1520 Bronson Road in Fairfield, is an exceptional example of a mid-1700s saltbox home. During the spring of 1750, newlyweds David and Jane Sturges Ogden moved into their new home on the road to Greenfield. They had reason to look forward to their future. Both came from established families who could afford to start them out well in life. Jane brought a reasonable dowry and David’s family provided the house and land. For the next 125 years it was home for the Ogden family in the farming and coastal shipping town of Fairfield. Today, the Ogden House retains its beautiful situation overlooking Brown’s Brook in the fertile Mill River Valley. It contains fine furniture, spinning wheels, tableware, iron pieces, textiles, and other objects from the Fairfield Museum collections. An eighteenth-century style kitchen garden behind the house is laid out symmetrically with raised beds. The garden features herbs typical of those used at the time, and is generously maintained by the Fairfield Garden Club. A bridge across the brook leads to a trail planted with native Connecticut wild flowers and shrubs. In 2013 an apiary was established to respond to the Honey Bee Colony Collapse Disorder and to signify the importance of beekeeping in colonial times. Bee pollination insured the garden’s productivity — the key to surviving in colonial New England.

1778

Smallpox Inoculation

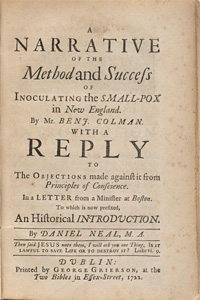

Inside the newly renovated Sun Tavern, located on the Museum Commons behind the Fairfield Museum, is an exhibition called “Seeking Justice,” featuring an area where visitors can review colonial cases and play the role of judge or defendant. A variety of scripts (and several judge’s robes!) are on hand. One of the cases showcased in the exhibition is a 1778 case against Peter Banks for illegal smallpox inoculation. Smallpox was the most feared disease in the American colonies. It was very contagious, and there was a major epidemic going on at the same time at the Revolutionary War. Inoculation was available starting in the 1720s. However, it was very controversial, because it involved exposing the person to a small dose of the infection in hopes that they would get a mild case of the disease and be immune after a few weeks of recovery. Inoculation was expensive, so it was not available to everybody. Also, people who had been inoculated were not always careful to stay isolated. The state passed a law making it illegal for civilians to be inoculated without permission: “And be it further enacted, That no person hereafter within the limits of any town in this state, shall receive, give or communicate the infection of the small-pox by way of inoculation… without first obtaining a certificate from the major part of the civil authority, and of the select-men of such town….” Peter Banks was accused of getting inoculated without obtaining a certificate. Should he have been found guilty? Visitors at Sun Tavern can “be the judge” and decide for themselves. In truth, Peter Banks did not even show up for his court appearance. However, the judge must have determined that Banks did not pose a significant danger to the community. The case against Banks was dismissed, although he did have to pay nine pounds, nine shillings, and eight pence to cover the court costs.

Inside the newly renovated Sun Tavern, located on the Museum Commons behind the Fairfield Museum, is an exhibition called “Seeking Justice,” featuring an area where visitors can review colonial cases and play the role of judge or defendant. A variety of scripts (and several judge’s robes!) are on hand. One of the cases showcased in the exhibition is a 1778 case against Peter Banks for illegal smallpox inoculation. Smallpox was the most feared disease in the American colonies. It was very contagious, and there was a major epidemic going on at the same time at the Revolutionary War. Inoculation was available starting in the 1720s. However, it was very controversial, because it involved exposing the person to a small dose of the infection in hopes that they would get a mild case of the disease and be immune after a few weeks of recovery. Inoculation was expensive, so it was not available to everybody. Also, people who had been inoculated were not always careful to stay isolated. The state passed a law making it illegal for civilians to be inoculated without permission: “And be it further enacted, That no person hereafter within the limits of any town in this state, shall receive, give or communicate the infection of the small-pox by way of inoculation… without first obtaining a certificate from the major part of the civil authority, and of the select-men of such town….” Peter Banks was accused of getting inoculated without obtaining a certificate. Should he have been found guilty? Visitors at Sun Tavern can “be the judge” and decide for themselves. In truth, Peter Banks did not even show up for his court appearance. However, the judge must have determined that Banks did not pose a significant danger to the community. The case against Banks was dismissed, although he did have to pay nine pounds, nine shillings, and eight pence to cover the court costs.

1784

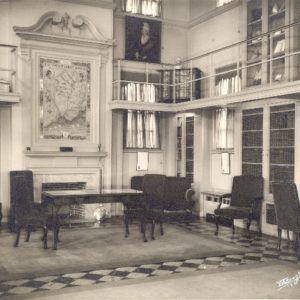

Born and raised in Setauket, Long Island, Caleb Brewster left his home at the age of 19, seeking adventure as a whaler. With war brewing, he returned in 1775 and joined the local militia, where he became a lieutenant. Looking for more action, in 1777, he joined the Second Continental Artillery. Stationed in Connecticut, he was able to take part in raids on British-held areas of Long Island. He also had a commission to operate as a privateer in Long Island Sound, capturing British vessels and provisions. In August 1778, Brewster wrote to George Washington from Norwalk, volunteering to spy on the enemy in Long Island. Washington eagerly accepted. Brewster is best known for the role he played in the Culper Spy Ring during the Revolutionary War. Operating out of Black Rock harbor in Fairfield from 1778 until 1783, Brewster engaged in many successful raids and expeditions against the British on Long Island, and carried intelligence across Long Island Sound to Washington’s headquarters. After the war ended, he married Anne Lewis and they settled in their own house in Black Rock. He opened a blacksmith shop near the wharves in Black Rock harbor, on what is now Brewster Street. A tall case clock that is housed in the Fairfield Museum’s library exhibition belonged to Brewster. He ordered it from local clockmaker Joseph Bulkley around the time he married Lewis, in 1784. It is the most sophisticated case of any known Bulkley clock; it is thought that the wood for the case was brought from Brewster’s property in Herkimer, New York.

Born and raised in Setauket, Long Island, Caleb Brewster left his home at the age of 19, seeking adventure as a whaler. With war brewing, he returned in 1775 and joined the local militia, where he became a lieutenant. Looking for more action, in 1777, he joined the Second Continental Artillery. Stationed in Connecticut, he was able to take part in raids on British-held areas of Long Island. He also had a commission to operate as a privateer in Long Island Sound, capturing British vessels and provisions. In August 1778, Brewster wrote to George Washington from Norwalk, volunteering to spy on the enemy in Long Island. Washington eagerly accepted. Brewster is best known for the role he played in the Culper Spy Ring during the Revolutionary War. Operating out of Black Rock harbor in Fairfield from 1778 until 1783, Brewster engaged in many successful raids and expeditions against the British on Long Island, and carried intelligence across Long Island Sound to Washington’s headquarters. After the war ended, he married Anne Lewis and they settled in their own house in Black Rock. He opened a blacksmith shop near the wharves in Black Rock harbor, on what is now Brewster Street. A tall case clock that is housed in the Fairfield Museum’s library exhibition belonged to Brewster. He ordered it from local clockmaker Joseph Bulkley around the time he married Lewis, in 1784. It is the most sophisticated case of any known Bulkley clock; it is thought that the wood for the case was brought from Brewster’s property in Herkimer, New York.

After Brewster died in 1827, the clock went to his grandson, Caleb Hackley, then to his great-great grandson, Samuel Brewster of Derby, Connecticut. A member of the Perry family—loosely connected to original clockmaker Joseph Bulkley—purchased it in 1935 and brought it back to Fairfield. Over the years the clock made its way out to Nevada, but in 2016 it was donated to the Fairfield Museum, bringing this splendid example of Fairfield clock-making back to its original home.

1785

Entertaining Taverns

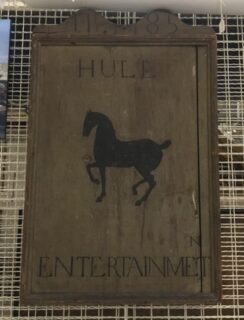

This 1785 sign from the Museum’s collection promising “Entertainment” marked Hull’s Tavern, which was built in 1772 by Lewis Goodsell (the son of Greenfield Hill’s first minister), and then operated by Stephen Hull. One memoir recalled the tavern on Hulls Highway in Greenfield Hill doing a brisk business, hosting regular dances with wine, plum cake, and a fiddler. It was one of several taverns in Fairfield in those years; in addition to Penfield’s Sun Tavern and Bulkley’s tavern near what is now Town Hall, Molly Pike ran a flourishing tavern in Southport and Knapp’s and Benson taverns also served the center of town. In colonial and early nineteenth-century Connecticut, travelers relied on painted signs such as this one to guide their journeys. Among Connecticut’s earliest laws was one requiring each town to have at least one inn that “passengers or strayngers may know where to resorte.” Innkeepers were regulated by the town and colony, which granted a license to people nominated by town leaders to keep a “public house” in an orderly fashion. In 1672 another law specified that each tavern was required to have “some suitable Signe set up in the view of all Passengers for the direction of Strangers where to go, where they may have entertainment.” The black horse on this sign was found on many tavern signs throughout the colonies and the word “entertainment” was used to convey that food and lodging were available within – “for Man and Horse,” as some other signs proclaimed. A passerby would recognize the imagery and know the building was a tavern, just as we recognize certain commercial logos today.

This 1785 sign from the Museum’s collection promising “Entertainment” marked Hull’s Tavern, which was built in 1772 by Lewis Goodsell (the son of Greenfield Hill’s first minister), and then operated by Stephen Hull. One memoir recalled the tavern on Hulls Highway in Greenfield Hill doing a brisk business, hosting regular dances with wine, plum cake, and a fiddler. It was one of several taverns in Fairfield in those years; in addition to Penfield’s Sun Tavern and Bulkley’s tavern near what is now Town Hall, Molly Pike ran a flourishing tavern in Southport and Knapp’s and Benson taverns also served the center of town. In colonial and early nineteenth-century Connecticut, travelers relied on painted signs such as this one to guide their journeys. Among Connecticut’s earliest laws was one requiring each town to have at least one inn that “passengers or strayngers may know where to resorte.” Innkeepers were regulated by the town and colony, which granted a license to people nominated by town leaders to keep a “public house” in an orderly fashion. In 1672 another law specified that each tavern was required to have “some suitable Signe set up in the view of all Passengers for the direction of Strangers where to go, where they may have entertainment.” The black horse on this sign was found on many tavern signs throughout the colonies and the word “entertainment” was used to convey that food and lodging were available within – “for Man and Horse,” as some other signs proclaimed. A passerby would recognize the imagery and know the building was a tavern, just as we recognize certain commercial logos today.

1815

Celebrating Peace on the Town Green

The Town Green has long been a place for a community celebration. In 1815, when news arrived that the War of 1812 was over, Fairfield organized an elaborate ox roast on the Green. People came from the different neighborhoods of Fairfield to this central spot. From Mill River (known as Southport today), forty boys towed a boat on runners, joining people from Greens Farms, Greenfield, Stratfield, and Black Rock. Eighteen blasts from a cannon in Black Rock were answered by eighteen blasts from a cannon on the Green, and in the evening, the Green was illuminated by fires from eighteen tar barrels piled in a pyramid, representing the 18 states of the union. The crowd heard remarks from local clergy inside the meetinghouse, sang psalms and hymns, and marched around the courthouse and the Fairfield Academy buildings. Then they enjoyed a celebratory dinner, feasting on the large ox that had been roasting since the day before in a pit dug for that purpose on the Green.

The Town Green has long been a place for a community celebration. In 1815, when news arrived that the War of 1812 was over, Fairfield organized an elaborate ox roast on the Green. People came from the different neighborhoods of Fairfield to this central spot. From Mill River (known as Southport today), forty boys towed a boat on runners, joining people from Greens Farms, Greenfield, Stratfield, and Black Rock. Eighteen blasts from a cannon in Black Rock were answered by eighteen blasts from a cannon on the Green, and in the evening, the Green was illuminated by fires from eighteen tar barrels piled in a pyramid, representing the 18 states of the union. The crowd heard remarks from local clergy inside the meetinghouse, sang psalms and hymns, and marched around the courthouse and the Fairfield Academy buildings. Then they enjoyed a celebratory dinner, feasting on the large ox that had been roasting since the day before in a pit dug for that purpose on the Green.

1848

The Train Comes to Town

On December 27, 1848, the first train run by the New York and New Haven Railroad Company passed through Fairfield, coming from New Haven on its way to New York. Many of the town’s residents did not greet this event with enthusiasm since it threatened to change their quiet way of life. In fact, the railroad’s impact was profound. Suddenly New York City was only a few hours away. Fairfield men could work in New York City and return the same day if they chose. The new mobility also affected women, who gained the freedom to visit friends and family in the city much more frequently. People who had previously grumbled about the construction of a railroad soon saw its advantages, including the economic benefits to the town.

On December 27, 1848, the first train run by the New York and New Haven Railroad Company passed through Fairfield, coming from New Haven on its way to New York. Many of the town’s residents did not greet this event with enthusiasm since it threatened to change their quiet way of life. In fact, the railroad’s impact was profound. Suddenly New York City was only a few hours away. Fairfield men could work in New York City and return the same day if they chose. The new mobility also affected women, who gained the freedom to visit friends and family in the city much more frequently. People who had previously grumbled about the construction of a railroad soon saw its advantages, including the economic benefits to the town.

1888

The Northrop Brothers Build a Cottage

Robert Manuel, a writer and actor who lived in the Sun Tavern property, had the Victorian Cottage and Barn built in 1888 for the use of the workmen on his farm. The cottage is a good example of the Carpenter Gothic style. The property was purchased by the Town of Fairfield in 1978 and was rescued from demolition in 1988 and restored gradually over time. The Fairfield Museum opened the “Kids Cottage” space in 2017, inviting young children and family members to explore the community through play.

Robert Manuel, a writer and actor who lived in the Sun Tavern property, had the Victorian Cottage and Barn built in 1888 for the use of the workmen on his farm. The cottage is a good example of the Carpenter Gothic style. The property was purchased by the Town of Fairfield in 1978 and was rescued from demolition in 1988 and restored gradually over time. The Fairfield Museum opened the “Kids Cottage” space in 2017, inviting young children and family members to explore the community through play.

1904

Preserving Fairfield’s History

The Fairfield Historical Society was organized in 1904. Originally part of the Fairfield Public Library, the organization collected books, documents and works of art and culture related to the history of Fairfield. Over time, the Historical Society grew and moved into its own building in 1954. In 2007 it opened a new building and became known as the Fairfield Museum.

The Fairfield Historical Society was organized in 1904. Originally part of the Fairfield Public Library, the organization collected books, documents and works of art and culture related to the history of Fairfield. Over time, the Historical Society grew and moved into its own building in 1954. In 2007 it opened a new building and became known as the Fairfield Museum.

1921

Fairfield Store Opens

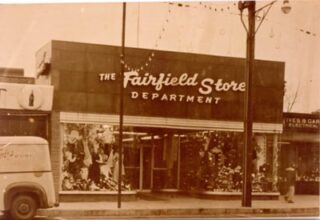

The Fairfield Department Store, a home-grown retail establishment on Post Road, was founded in 1921 by brothers Samuel and Isadore Manasevit. The original store primarily carried menswear and work-related apparel to meet the needs of the population, the majority of whom worked in factories. Isadore’s son, Frank, and Samuel’s son, Stanley, officially entered the business in 1947. In 1956, the cousins expanded the store, making it the first two-story building in Fairfield. In 1966, the owners changed the name of the store to simply “The Fairfield Store.” Two years later, the store expanded into the former Woolworth’s building and the owners renovated the exterior. The Fairfield Museum collection contains advertising and promotional materials donated by the management of the Fairfield Store, which closed in 1996.

The Fairfield Department Store, a home-grown retail establishment on Post Road, was founded in 1921 by brothers Samuel and Isadore Manasevit. The original store primarily carried menswear and work-related apparel to meet the needs of the population, the majority of whom worked in factories. Isadore’s son, Frank, and Samuel’s son, Stanley, officially entered the business in 1947. In 1956, the cousins expanded the store, making it the first two-story building in Fairfield. In 1966, the owners changed the name of the store to simply “The Fairfield Store.” Two years later, the store expanded into the former Woolworth’s building and the owners renovated the exterior. The Fairfield Museum collection contains advertising and promotional materials donated by the management of the Fairfield Store, which closed in 1996.

1959

John Sullivan Elected

John Sullivan served as the first selectman for 24 years, from 1959 to 1983. An Irish-Catholic Democrat, his election in 1959 was a significant departure from the previous Yankee-Protestant leadership. He was once quoted as saying about Fairfield: “The political climate was strictly Republican. This was a Republican town. You could have your friends Republican and your friends Democrat and you could assimilate together and be friends, social and all that. But it was there. When they went to vote that was all there was to it.” Sullivan’s leadership during the 1960s and 1970s helped guide Fairfield through a period of rapid growth and planning.

John Sullivan served as the first selectman for 24 years, from 1959 to 1983. An Irish-Catholic Democrat, his election in 1959 was a significant departure from the previous Yankee-Protestant leadership. He was once quoted as saying about Fairfield: “The political climate was strictly Republican. This was a Republican town. You could have your friends Republican and your friends Democrat and you could assimilate together and be friends, social and all that. But it was there. When they went to vote that was all there was to it.” Sullivan’s leadership during the 1960s and 1970s helped guide Fairfield through a period of rapid growth and planning.

1960

Building a Bomb Shelter

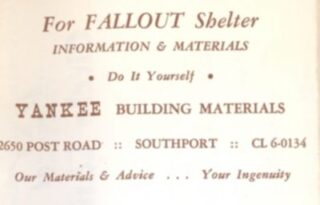

Some long-time residents remember when Fairfield Hardware opened a demonstration bomb shelter, buried next to the store. People climbed down the metal ladder to get to the shelter, which had a bunk bed, table, and storage for canned food, water and supplies. At a time when the Cold War was heating up, especially leading up to the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, fears of nuclear war were high and many residents were interested in the bomb shelter.

Some long-time residents remember when Fairfield Hardware opened a demonstration bomb shelter, buried next to the store. People climbed down the metal ladder to get to the shelter, which had a bunk bed, table, and storage for canned food, water and supplies. At a time when the Cold War was heating up, especially leading up to the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, fears of nuclear war were high and many residents were interested in the bomb shelter.